The Lie You Were Told About Academic Productivity

Building Sustainable Habits That Last (Part 1 of 2)

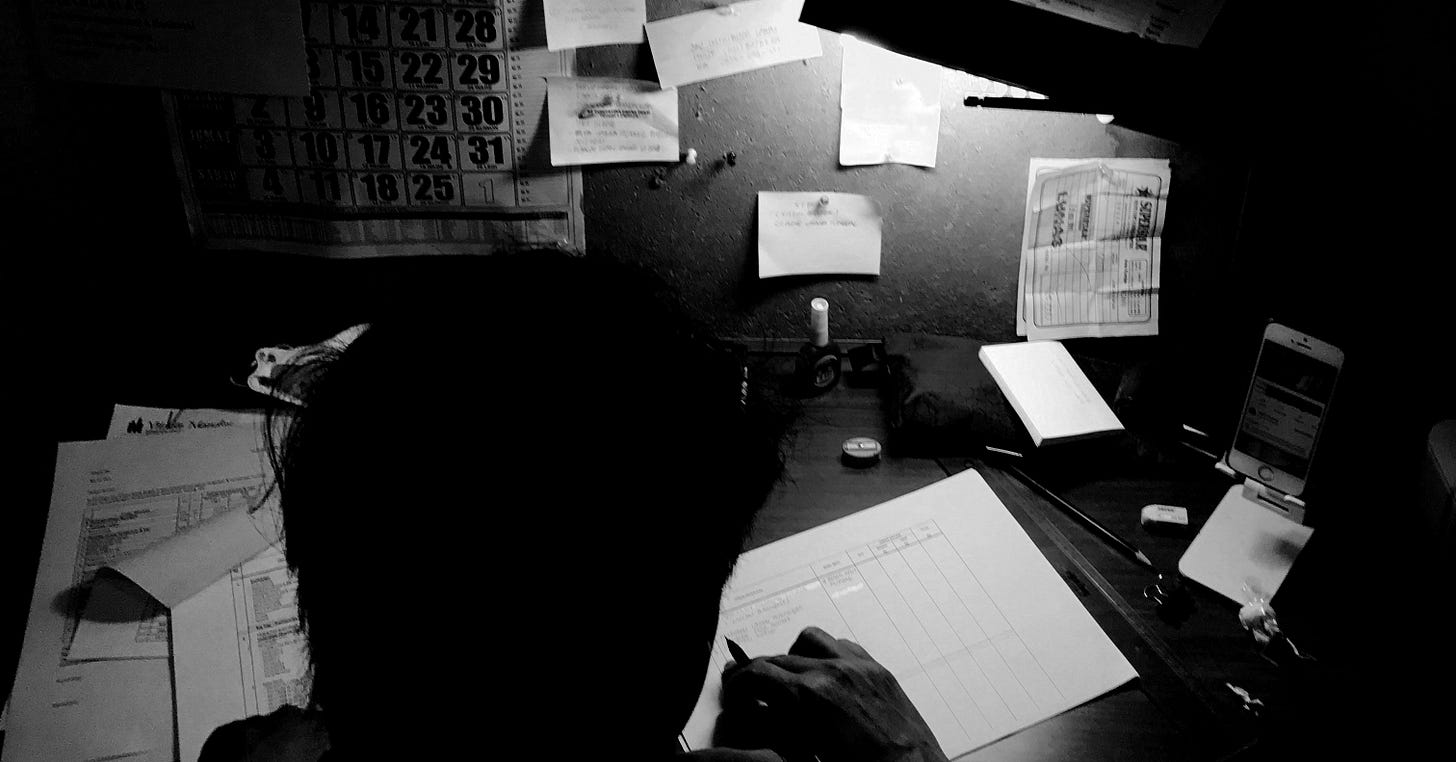

It was 11:47 PM on a Sunday, and I was still grading papers.

Seventy-three contracts exams from the previous semester sat in a stack on my desk. Exams I’d been successfully avoiding all winter break with increasingly creative excuses. I only had a few left to finish. But my eyes burned from the screen. My back had filed a formal grievance against my dining room chair.

And somewhere underneath the lukewarm coffee and the bubbling anxiety was an awareness that the spring semester was starting in a few day and I hadn’t touched my lecture notes.

There’s something that nobody tells you when you’re just getting started on the tenure track. When a pattern repeats itself enough times, it stops feeling like a crisis and starts feeling like a personality trait.

I had convinced myself that this was simply how academic life worked. Feast or famine, sprint and crash, the heroic all-nighter followed by the inevitable collapse. I wore the exhaustion like a credential, like a red badge of courage on my sleeve.

I was a law professor who taught my students that excellence demanded proper planning and discipline. And yet here I was, managing my own professional life like a series of car accidents, each one survived, none of them prevented.

That Sunday night, as I sat there, barely able to focus on the words in front of me, I decided that something had to change.

What followed was several months of completely rethinking how I approached academic work. I became intensely focused less on the big strategic decisions, and more on the small daily habits that I learned either support your capacity for good work or quietly erode it. And what I discovered surprised me.

Sustainable academic success has far less to do with discipline, willpower, or grinding than we like to believe. It is much more about understanding the rhythms that your mind and body actually need, and building small, consistent practices around them.

I want to share what I learned.

But first, we need to name the thing that’s been working against you.

The Story Academia Tells About Itself

There is a mythology embedded in academic culture, and if you’ve been in this world for any length of time, you’ve absorbed it whether you meant to or not.

It goes something like this: meaningful scholarly work requires sacrifice.

The most serious scholars are the ones who work the hardest, sleep the least, and let everything else in their lives fall into second place. The cluttered office is a sign of an active mind. The canceled dinner is evidence of commitment. The 80-hour work week is the price you pay for doing important scholarship.

You have seen this story performed.

Maybe you had a professor who wore exhaustion as a badge of honor, who seemed to believe that suffering and seriousness were synonyms. Maybe you watched senior colleagues model a version of success that looked, from the inside, like a slow emergency. Maybe you’ve already started to perform this story yourself, because it’s the water you swim in and you didn’t have another model.

I want to be direct with you. This narrative is wrong, and it’s counterproductive to the goals it claims to serve.

The neuroscience and performance psychology research on this is clear and has been for decades, even if academia has been slow to apply it. Our best creative and analytical work—the kind of thinking that produces original scholarship, that makes unexpected connections, that sustains a genuine argument—emerges from well-rested, balanced minds.

Chronic stress doesn’t make your scholarship sharper. It makes it shallower. It increases error rates, narrows creative range, and degrades the kind of sustained focus that real intellectual work requires.

The habits that get you through graduate school or through a brutal submission deadline are not the same habits that will sustain decades of productive scholarship. You can sprint through a crisis. But you cannot sprint through a career.

The academics I have watched produce consistently excellent work over long periods of time share certain qualities that don’t get talked about nearly enough. They have strong boundaries. They rest without guilt. They have lives that exist outside their work.

They manage their energy like the finite, precious resource it is, and they do so without apology.

What Sustainable Performance Actually Requires

When I started reading the research on long-term high performance, I kept encountering a framework that felt almost embarrassingly simple, but that explained almost everything about why I kept crashing.

Sustainable performance depends on managing not just your time but your energy.

Physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual energy. When any one of these systems becomes chronically depleted, your capacity for quality work diminishes in ways that no amount of extra hours can compensate for.

Physical energy is the foundation. And it’s the one academics are most likely to treat as optional. Your brain is an organ. It runs on sleep, food, water, and movement. The romantic image of the scholar sustained by coffee and good ideas is both unhealthy and intellectually inefficient. A tired brain is a slow brain, a less creative brain, a brain more likely to miss the flaw in an argument or fail to see the connection between ideas. Sleep deprivation impairs cognitive function in ways that closely resemble mild intoxication, and like intoxication, it also impairs your ability to perceive how impaired you actually are.

Emotional energy comes from the parts of life that have nothing to do with work: supportive relationships, activities that bring pleasure, healthy ways of processing the stress that academic life generates. Isolation is a creativity killer. The colleague who never leaves the office, never talks to anyone outside the department, never does anything that isn’t directly career-adjacent, that person is not maximizing their scholarly output. They are slowly depleting the emotional reserves that make sustained intellectual engagement possible.

Mental energy refers to your capacity for focused, demanding cognitive work. This capacity is not infinite, and it cannot be replenished simply by stopping work. It requires genuine rest—sleep, time in nature, meditation, whatever form of restoration works for your nervous system. The key word is genuine. Scrolling on your phone for an hour is a different kind of stimulation, not rest. Your brain needs something closer to actual silence.

Spiritual energy, as researchers use the term, doesn’t necessarily mean anything religious. It means connection to purpose and meaning. The sense that what you’re doing matters, that it connects to something larger than the next deadline or the next publication. This is why clarifying your deeper motivations as a scholar is so important. Purpose-driven work is inherently more sustainable than work motivated purely by anxiety or external reward. Fear is a powerful short-term motivator but a terrible long-term fuel.

These four energy systems are deeply interconnected.

Neglect one, and the others suffer. Nurture all four, and they create deep engagement rather than slow depletion.

From Deadline-Driven to Rhythm-Driven

The single biggest shift I made in my own approach was moving from what I’d call a deadline-driven work style to a rhythm-driven one.

In the deadline-driven model—which is the default mode of most academics—you work intensively when a project demands it, then recover during lighter periods. The problem is that these cycles are rarely as clean as they sound.

The “lighter periods” fill up with other demands. Recovery never quite happens. The feast-or-famine rhythm leaves you either overwhelmed or anxiously waiting for the next crisis, with no sustainable middle ground in between.

In a rhythm-driven model, you establish consistent daily and weekly patterns that allow for steady progress on what matters most while preserving energy reserves for the unexpected. There are no identical days. Academic life has real fluctuations, and any sustainable system has to accommodate them. The goal is a baseline. Certain practices that remain consistent regardless of what else is happening, and that provide structural stability when the external environment gets chaotic.

Think of it like this: a ship doesn’t fight the weather by being rigid. It maintains its heading by having a reliable keel. Your daily and weekly rhythms are the keel. They don’t prevent the storms. They keep you oriented through them.

In practice, this means building your days around a few non-negotiable anchor points, such as a morning routine that transitions you into work mode rather than dropping you into chaos. It means establishing protected time for your most important scholarly projects before the day gets away from you.

It means implementing some form of physical movement on a regular basis. And, it means having an evening routine that actually closes the workday rather than letting it bleed indefinitely into the night.

These don’t have to be elaborate. Consistent matters far more than complex.

At the weekly level, this means treating restoration as a genuine priority rather than something that happens when everything else is done (which means it never happens). One day—or the equivalent spread across a couple of days—dedicated to actual rest. No work email. No academic tasks. Activities that restore rather than deplete. Time with people who aren’t part of your professional world. Engagement with ideas that have nothing to do with your research.

This is maintenance, and it deserves to be treated as such.

The Power of Embarrassingly Small Habits

Here is the thing about ambitious habit-change plans: they fail.

The people who make them aren’t lacking in discipline. The plans just require too much willpower to maintain consistently, especially during the high-stress periods when you need them most.

The approach that actually works feels almost embarrassingly simple by comparison. It’s built on what researchers call micro-habits—behaviors so small that they require virtually no willpower, but whose cumulative effects over months and years are genuinely transformative.

I’ll give you my own examples:

Every morning, I take 5–10 minutes to review my schedule for the day and reaffirm my goals so I know exactly what matters.

I exercise almost every day. At a minimum, I lift weights three days a week, and I run two to three days a week.

When I get home, I have dinner with my family and spend time getting my kids ready for bed while intentionally not thinking about work.

In the evening, I read for fun for at least twenty minutes before bed.

On the weekends, I intentionally rest. I watch movies with my wife, play with my kids, and practice our faith.

On Sunday evenings, I map out my goals for the week and review what I accomplished the week before.

I use a time blocker on my phone to limit my daily social media engagement.

None of these habits are dramatic. But together, they create a rhythm. A set of small, reliable anchors that define the texture of every day.

The habits work because they’re sustainable. You don’t have to be at your best to do them. You can maintain them during a brutal semester, a difficult stretch of rejection, or a period when everything else has gone sideways. And because you can maintain them consistently, they compound.

Three months of small daily improvements in sleep, movement, and intentional rest creates exponential benefits, the kind that sneak up on you.

Your Homework

Before we go any further, I want you to do something concrete.

The insights in Part Two will be far more useful to you if you arrive there with actual data about yourself rather than assumptions.

Track your energy for seven days. Three times a day—morning, afternoon, and evening—record a simple 1-10 score. You don’t need an app or a system. A note on your phone, a line in a journal, a sticky note on your desk will do.

Add brief context to each number. Jot a sentence about what you’ve been doing, eating, or experiencing in the hours before. Note your sleep duration and quality. Note when you exercised, if you did. Flag which meetings, conversations, or tasks left you feeling drained versus energized.

At the end of the week, look for patterns. When are your natural energy peaks? What activities consistently deplete you more than they seem like they should? What are you doing differently on your good days versus your difficult ones?

This is about understanding your own rhythms well enough to stop working against it. Because that’s what most of us are doing. Not through any failure of character, but simply because nobody ever showed us another way.

Part Two is about building the specific system that will serve you across the full arc of a scholarly career. But that system has to be built around your actual patterns, not a generic template.

The energy audit is how you get that information.

One week. Seven numbers per day.

That’s it.

Becoming Full,

P.S. As always, thank you for reading this week’s issue of The Tenure Track. If you found this article helpful, share it with a friend. If it moved you, consider supporting with a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. Together, let’s continue to build a supportive and creative academic community.

Your support helps me create content that serves fellow scholars on the path.