Building a Writing Pipeline That Works (Part 1)

Why Productivity Isn’t the Problem

Three years ago, I met a brilliant scholar at a conference who seemed to have everything figured out. They had tenure at a prestigious institution, a book contract with a top university press, and ideas that sparked conversations.

But when I asked what they were writing right now, something shifted.

“I have seventeen different drafts sitting on my computer,” they said. “Some are nearly finished. Others are outlines. I start new projects because I’m genuinely excited about the ideas, but I can’t seem to finish anything anymore.”

They paused, then added the sentence that stayed with me:

“I feel like I’m drowning in my own productivity.”

That feeling is far more common than we admit, especially among scholars who care deeply about their work and who have reached a stage where ideas arrive faster than time allows.

At some point, the problem stops being motivation. It stops being discipline.

And it certainly stops being intelligence.

The problem becomes structural.

When Ideas Outpace Structure

Early in an academic career, scarcity dominates.

You are searching for ideas worth pursuing. You worry about whether you belong. You measure progress in small wins: a conference acceptance, a draft chapter, a revise-and-resubmit offer.

Later, abundance takes over.

You begin to see connections everywhere. Every conversation sparks a new line of inquiry. Every article you read suggests a counterargument or extension. Invitations arrive faster than you can accept them.

Academic culture offers little guidance for this transition.

We are trained to complete projects, not to manage portfolios of ideas across time. We are taught how to write, but not how to decide what deserves sustained attention.

So most scholars default to what they know:

project-by-project thinking.

The Limits of Project-Based Writing

Project-based thinking treats each piece of writing as a self-contained event.

You conceive it, research it, write it, submit it, and move on. This works, until it doesn’t.

As your intellectual life expands, project-based thinking produces a familiar pattern:

Promising ideas are started impulsively

Drafts accumulate without clear priority

Older projects lose momentum but retain guilt

New ideas feel urgent precisely because they are untouched

The result is not laziness.

It is overload.

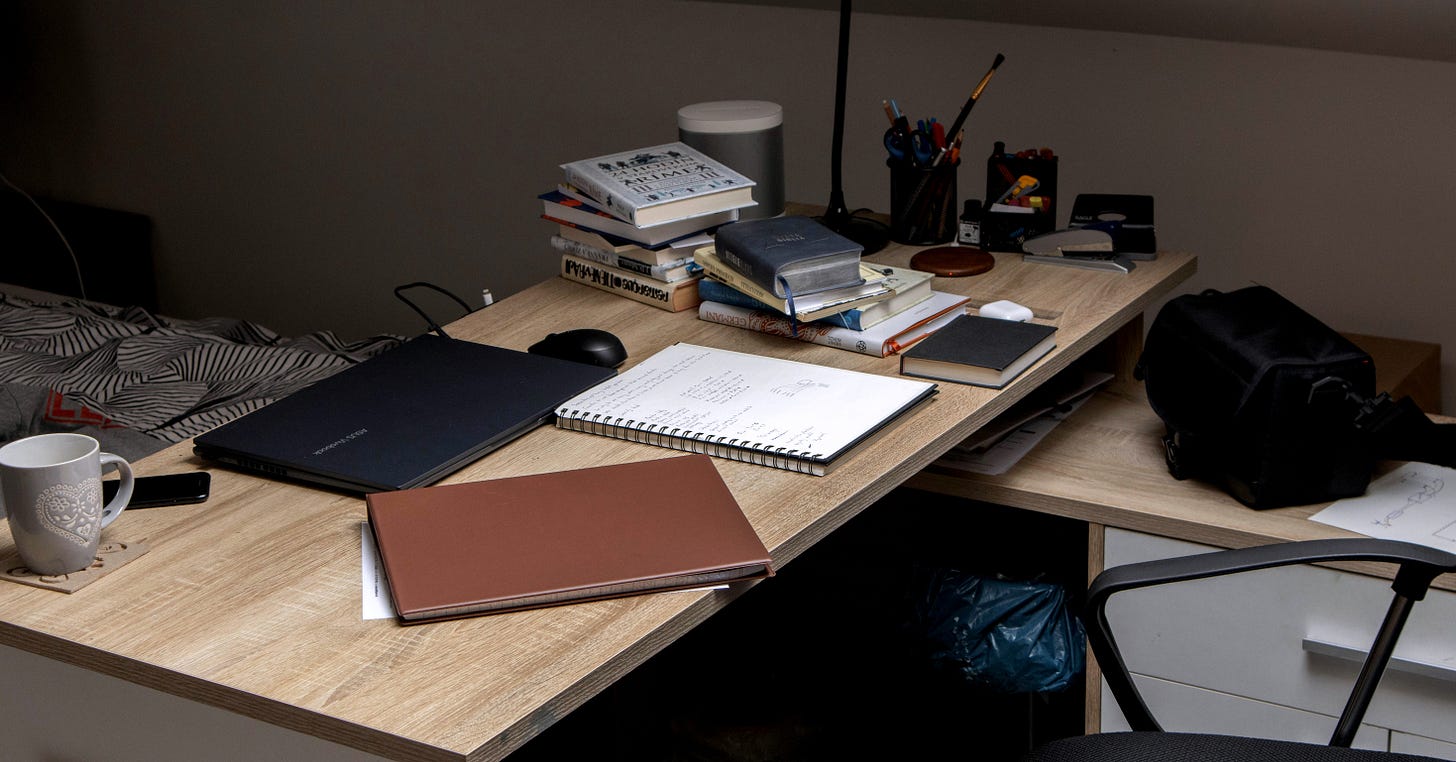

Consider what often lives on a mid- or senior-career scholar’s hard drive:

A dozen articles at various stages of completion

Several conference papers that were never fully written

Folders labeled “book ideas,” “future projects,” or “next summer”

Half-developed grant proposals

Notes scattered across documents, notebooks, and apps

Each of these represents genuine intellectual labor.

But without a governing system, they begin to compete with one another rather than build toward something coherent.

Over time, this competition creates paralysis. Progress slows not because nothing is happening, but because too much is happening without direction.

Why Impact Requires a Pipeline

The scholars who consistently finish meaningful work tend to share one quiet habit: they stop treating ideas as emergencies.

Instead, they adopt a pipeline mindset.

A writing pipeline does not reduce creativity. It protects it by giving ideas room to mature without demanding immediate execution.

It acknowledges that ideas move through phases, and that different phases require different kinds of attention.

The core shift is simple but profound:

Instead of asking “What am I writing?”

you begin asking “Where is this idea in its life cycle?”

This reframing does several important things at once:

It removes moral judgment from unfinished work

It replaces guilt with clarity

It allows you to hold many ideas without trying to write all of them at once

A pipeline turns chaos into flow.

The Four Stages of Scholarly Development

Every piece of writing—no matter how polished—moves through the same basic stages. The pipeline simply makes those stages visible and intentional.

Stage 1: Ideation and Capture

This is the stage of possibility. Ideas arrive incomplete, often sparked by reading, conversation, teaching, or current events.

The mistake many scholars make here is commitment: treating every interesting idea as a future obligation.

In a pipeline, Stage 1 is expansive but light.

Typical activities include:

Reading widely and taking generative notes

Capturing ideas quickly without polishing them

Noticing connections to your broader scholarly interests

Asking whether an idea aligns with your long-term direction

The goal is not development.

The goal is capture without pressure.

The most effective output at this stage is a short project outline, just enough to preserve the idea without inflating it. Most ideas should stay here longer than you think.

Stage 2: Development and Testing

Stage 2 is where discernment begins. Here, ideas are stress-tested before they are granted the privilege of full drafting.

This is often the most neglected stage in academic writing, even though it is the one that saves the most time in the long run.

Stage 2 work often includes:

Focused literature review

Developing a provisional framework or argument

Presenting the idea at a conference or workshop

Talking through the project with trusted colleagues

Drafting a detailed outline rather than a full manuscript

The question guiding this stage is simple but demanding:

Is this idea strong enough—and aligned enough—to justify sustained attention?

Many projects should end here.

That is not failure.

That is wisdom.

Stage 3: Production and Refinement

Stage 3 is where most scholars believe writing begins.

In reality, it is where writing becomes expensive.

Drafting requires concentration, emotional energy, and tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. This is why pipelines limit how many projects can occupy this stage at once.

Stage 3 typically involves:

Full drafting

Argument refinement

Data analysis

Peer feedback

Revision cycles

Coordination with co-authors

Because of the demands involved, this stage benefits most from structure, boundaries, and realistic timelines.

Stage 4: Publication and Amplification

Stage 4 is where work leaves your desk and enters the world.

This stage includes:

Journal or press selection

Submission and revision management

Responding to peer review

Publication timelines

Post-publication engagement and visibility

Many scholars underestimate this stage, assuming that submission marks the end. In reality, how you manage Stage 4 determines whether your work quietly appears, or meaningfully circulates.

What Changes When the Pipeline Is in Place

When scholars adopt a pipeline approach, several shifts occur almost immediately.

They stop feeling guilty about unfinished work because unfinished work is now expected. They begin finishing more projects, not because they work harder, but because fewer projects are competing for deep attention.

And, perhaps most importantly, writing begins to feel calmer.

Not easier, but steadier.

The anxiety of “I should be working on everything” gives way to the clarity of

“I know what deserves my attention right now.”

Homework: Seeing Your Work Clearly

The goal of this assignment is not to fix your writing habits. It is to make your intellectual landscape visible.

Step 1: Conduct a Project Inventory

Set aside 30–45 uninterrupted minutes. Open a blank document and list every writing project you have started or seriously contemplated in the past two years. Include:

Articles

Book chapters

Book proposals

Conference papers

Grant applications

Public-facing essays

Collaborative projects that depend partly on you

Do not evaluate or edit the list. The task is honesty, not judgment.

Step 2: Assign Each Project a Pipeline Stage

Next to each project, label its current stage:

Stage 1 – Ideation and Capture: an idea, notes, or a brief outline

Stage 2 – Development and Testing: substantial research, outline, or presentation, but no full draft

Stage 3 – Production and Refinement: drafting or revising a full manuscript

Stage 4 – Publication and Amplification: submitted, under review, accepted, or published

Resist the urge to “upgrade” projects. Where a project actually sits matters more than where you want it to be.

Step 3: Notice the Pattern

Once everything is labeled, pause and reflect:

Where do most of your projects cluster?

Which stage feels most crowded—or most neglected?

Are there projects sitting in Stage 3 that have been there far longer than expected?

Write a short paragraph answering this question:

What does this inventory reveal about how I currently relate to my ideas and my time?

That paragraph—not the list—is the real work.

From Structure to Stewardship

A writing pipeline is not about productivity for productivity’s sake.

It is about stewardship of your ideas, your energy, and your scholarly life.

In Part 2 next week, we’ll turn from structure to practice: how scholars actually manage their pipelines week to week, how they avoid the subtle traps that stall progress, and how the system must evolve as careers mature.

Because naming a pipeline is only the beginning.

Learning how to live inside it is the real work.

Stay tuned!

Becoming Full,

P.S. As always, thank you for reading this week’s issue of The Tenure Track. If you found this article helpful, share it with a friend. If it moved you, consider supporting with a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. Together, let’s continue to build a supportive and creative academic community.

Your support helps me create content that serves fellow scholars on the path.

Bro, I loved this!!!!!!!